A new phase of geopolitical contestation is unfolding across Africa — one that bears resemblance to the Cold War rivalry of the twentieth century, yet differs in structure, motivation, and complexity. This emerging contest is less defined by ideological polarization and more by strategic competition over resources, markets, and influence. Its multiplicity of actors and fluid alliances make it potentially more volatile than the bipolar standoff that shaped global politics in the latter half of the last century.

Unlike the earlier era dominated by two superpowers, today’s environment reflects a crowded and overlapping field of state and non-state competitors. The United States and China are locked in competition for strategic access and economic leverage, while Russia and France — with Ukraine entangled through its wider geopolitical alignments — vie for influence in security and political domains. Regional actors such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates compete for economic and diplomatic footholds, and Turkey’s expanding presence intersects with Israel’s own strategic engagements. Beyond these visible rivalries lie shifting, pragmatic partnerships that defy fixed alignment and complicate the continent’s geopolitical landscape.

At the core of this contest is the pursuit of advantage across multiple domains. Critical minerals essential for modern industrial and digital economies have become central targets, alongside agricultural land and other natural resources. Diplomatic influence in multilateral forums, access to Africa’s expanding consumer markets, and the projection of strategic power — often framed in zero-sum terms — further drive the competition. The continent’s demographic growth and resource wealth have made it a central arena for global positioning.

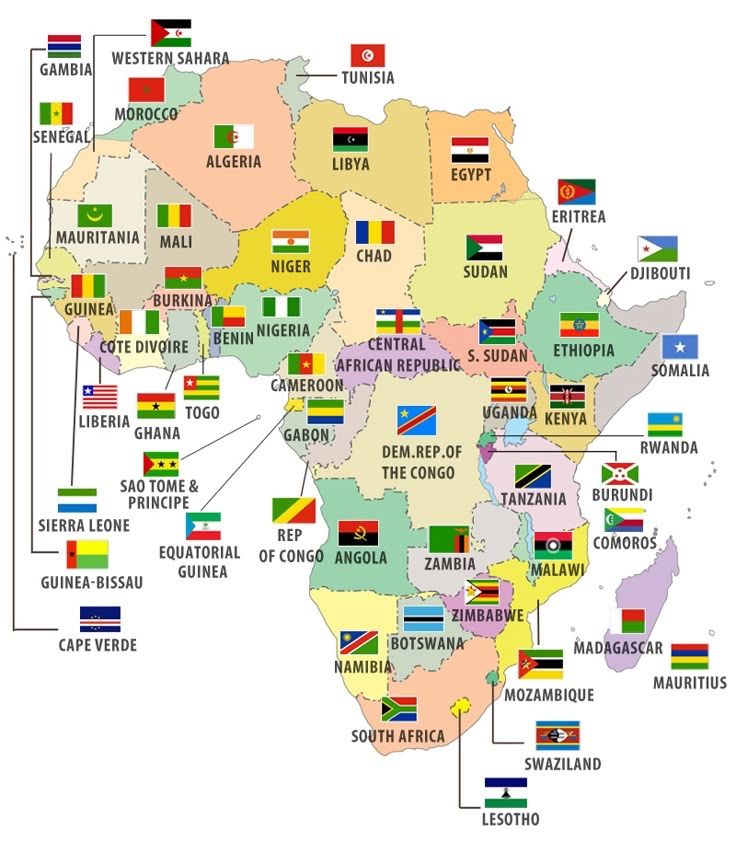

The rivalry manifests across several geographic theatres. Sudan and the wider Horn of Africa represent one of the most visible arenas, alongside the Democratic Republic of Congo and the broader Great Lakes region. The Sahel remains a focal point of security and influence struggles, while Libya continues to reflect overlapping external interests. Strategic mineral zones such as the Copperbelt in south-central Africa and the littoral states along the Gulf of Guinea — vital for maritime access and energy flows — also feature prominently in this evolving geopolitical contest.

The instruments employed are diverse and often hybrid in nature. Security cooperation agreements and military training initiatives coexist with resource-linked commercial arrangements and counter-deals. Private security actors increasingly operate alongside state forces, while diplomatic incentives — ranging from infrastructure commitments to political support — shape alignment decisions. These tools blur traditional boundaries between economic engagement, diplomacy, and security strategy.

Certain patterns signal the entrenchment of this competitive dynamic. Protracted civil conflicts in places such as Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo demonstrate how local crises intersect with external interests. The arming of state and non-state actors, persistent diplomatic frictions across subregions, and intensifying humanitarian emergencies point to systemic strain. Interstate tensions across the Horn of Africa, the Great Lakes region, and parts of West Africa underscore the wider implications of competing external engagements.

This new geopolitical environment differs fundamentally from the Cold War that preceded it. The absence of a clear ideological divide removes the binary clarity that once structured alliances. Instead, a multiplicity of actors operate simultaneously, alliances shift according to immediate strategic calculations, and advanced autonomous or semi-autonomous weapons technologies — particularly drone systems — introduce new operational risks. The contest is driven less by ideology than by material interests and strategic positioning. Moreover, African states now operate in a context of long-established sovereignty, leaving them with agency and responsibility in navigating external engagement.

Africa’s emerging Cold War is therefore not merely a replay of history but a transformation of it — multipolar, transactional, and resource-centered. Its trajectory will depend not only on the ambitions of external powers but also on the strategic coherence, governance choices, and diplomatic agency of African states themselves. Whether the continent becomes a battleground for competing interests or a negotiating space where partnerships are leveraged for development remains a defining question of the coming decades.

Owusu wrote this in synopsis format on his LinkedIn page