Global climate plans will cut emissions by just 2.6% by 2030, falling 40% short of what’s needed to keep a future within the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C goal alive, according to a report released Monday by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The combined emissions cut by the national climate plans, known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs), have increased by a mere 0.6% since last year, an insignificant change that will not affect global warming trajectories, the UN climate body said in its annual assessment ahead of next month’s COP29 summit in Baku.

“Current national climate plans fall miles short of what’s needed to stop global heating from crippling every economy and wrecking billions of lives and livelihoods across every country, said Simon Stiell, UNFCCC’s executive secretary. “Greenhouse gas pollution at these levels will guarantee a human and economic trainwreck for every country, without exception.”

As countries prepare to update their climate pledges ahead of next year’s COP30 in Brazil, time is running out to take the existential scale of the threat seriously. Since COP28, where countries adopted the UAE consensus reaffirming the 1.5ºC target established in 2015, only one nation has submitted updated climate plans under the treaty framework.

The UNFCCC’s dire assessment mirrors findings released last week by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), which reported that no policies with “significant implications for global emissions” were implemented globally in 2023, putting the world on course for “catastrophic” warming of 3.1ºC by the end of the century.

UNEP maintains that the 1.5ºC target – which its director called “one of the greatest asks of the modern era” – remains “technically possible” if there is “immediate global mobilisation on a scale and pace only ever seen following a global conflict.”

With global emissions set to exceed 1.5ºC of warming by 2050 – and a one-in-three chance of breaking 2ºC – UNEP’s chief called for a “quantum leap” in climate policy.

Stiell echoed this urgency, demanding an immediate end to the “era of inadequacy” — and for “a new age of acceleration” to begin at next month’s COP29.

“The last generation of NDCs set the signal for unstoppable change,” Stiell said. “New NDCs next year must outline a clear path to make it happen – by scaling up renewable energy, strengthening adaptation and accelerating the transition to low-carbon economies everywhere.”

The latest warning shot

With COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, just weeks away, a raft of new climate research has reinforced the alarm bells set off by the UNFCCC’s findings.

Planet-warming greenhouse gases surged to record highs in 2023, reaching levels unprecedented in human history, new data released by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) revealed on Monday.

The UN weather agency found carbon dioxide concentrations rose more than 10% in the past decade, while methane and nitrous oxide, short-lived but powerful greenhouse gases, also saw significant increases.

Carbon dioxide levels are now 51% higher than in pre-industrial times, when humans began burning fossil fuels at scale, while methane levels have risen 161% and nitrous oxide 25% over the same period, locking Earth’s atmosphere into a warming trajectory for at least the lifecycle of these gases.

“Another year. Another record,” said WMO secretary-general Celeste Saulo. “These are more than just statistics. Every part per million and every fraction of a degree temperature increase has a real impact on our lives and our planet.”

“This should set alarm bells ringing among decision-makers,” Saulo said.

Carbon dioxide is accumulating “faster than any time experienced during human existence” due to “stubbornly high fossil fuel” emissions, widespread forest fires, and a likely reduction in the ability of natural carbon sinks — such as oceans and forests — to absorb CO2, WMO said.

The 2023 increase of 2.3 parts per million marked the 12th straight year of rises above 2ppm – a rate of increase that would have taken centuries to occur naturally before industrialization.

“The record levels of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere are the logical outcome of the record amounts of greenhouse gases that our economies continue to dump into our ambient air,” Joeri Rogelj, a climate scientist at Imperial College London and lead author of the report, told the Guardian. “This doesn’t need to be the end of the story.”

Earth’s systems near breaking point

The WMO report raises fresh alarms about nature’s carbon sinks — oceans, forests, plants and soil that absorb carbon dioxide — and it isn’t alone. Earlier this month, international researchers released preliminary findings indicating forests, plants and soil absorbed almost no net carbon in 2023, suggesting they could be nearing a tipping point.

These natural buffers, long taken for granted in climate models, may be failing. Earth’s natural carbon sinks absorb nearly 50% of our carbon emissions, and their collapse could be catastrophic and rapidly accelerate global warming beyond current worst-case scenario projections.

“We see a sudden drop of the land carbon sinks from extreme warming and Amazon mega-drought,” said Philippe Ciais, one of the report’s lead authors. “If this decline continues, we may see a rapid acceleration of CO2 and global warming which was unforeseen in future climate models’ projections.”

Collapse of Atlantic current

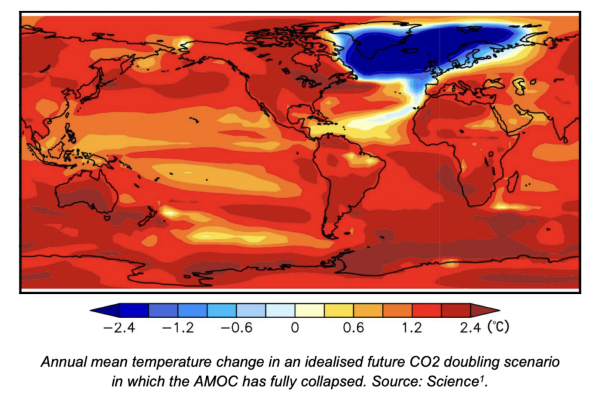

Meanwhile, 40 of the world’s leading experts on ocean and climate science penned an urgent open letter presented at the Arctic Circle conference in Iceland last week warning that the risk of collapse of a vital Atlantic current system, known as the AMOC, has been “greatly underestimated.”

The collapse of this system, one of the planet’s largest arteries transporting heat around the world’s oceans, would have “potentially catastrophic consequences” and trigger “devastating and irreversible climate impacts,” the letter warned.

The worst impacts would be felt in Nordic countries and “potentially threaten the viability of agriculture in northwestern Europe,” while global impacts would include reduced CO2 absorption by oceans, major sea-level rise, and a shift in tropical rainforest belts, meaning rains would no longer fall on the forests they keep alive – triggering droughts above rainforests vital to absorbing CO2 – and flood the new regions they settle over.

“This has happened repeatedly in Earth’s history, most recently during the last ice age,” Stefan Rahmstorf, a signatory of the open letter and head of the Earth system analysis department at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, said in an interview with the Guardian.

“These are among the most massive upheavals of climate conditions in Earth’s history,” Rahmstorf said. “I am now very concerned that we may push Amoc over this tipping point in the next decades. If you ask me my gut feeling, I would say the risk that we cross the tipping point this century is about 50/50.”

“We don’t know where the tipping point is.”

Image Credits: RecondOil.