This article, “Why Nigeria must imbibe ‘tax me, I task you’ culture”, was first published on March 15, 2018. Amidst a theoretical economic recession, primarily caused by plunging oil prices and a history of incompetence, Nigeria turned to debt and bond instruments to finance a portion of its 2017 budget (and later 2018). However, this development has failed to sustain the extremely ambitious and highly controversial 7 trillion naira budget.

Financing maturities have been sourced through further accumulation of debt, which, in the long run, could be offset by higher taxes or, in our case, just taxes. Implementing sound tax policies—not just to service ensuing debts but also to expand fiscal policy capabilities—should have always been a priority. However, compliance has, in reality, been unduly neglected.

With a 6% compliance rate recently revealed by the Minister of Finance, Nigeria has remarkably beaten its revenue target annually since the early 2000s, despite a steady GDP output (an average increase of 5.7% over the last ten years). However, Nigeria’s tax income has not increased accordingly over the years, most notably declining in certain years (see 2009, 2013, 2014). This raises the question of whether we have been adhering to some form of unheralded trickle-down economics with a non-compliance clause.

With the population growing at almost 3% annually over the past ten years—and recently outpacing GDP growth, evidently due to the recession and an increasing unemployment rate (currently over 18%)—the country could be susceptible to the effects of the Malthusian theory. Resources are not being adequately utilized, there is a huge gap in income distribution, and income per capita remains relatively low. Most importantly, the population continues to grow rapidly.

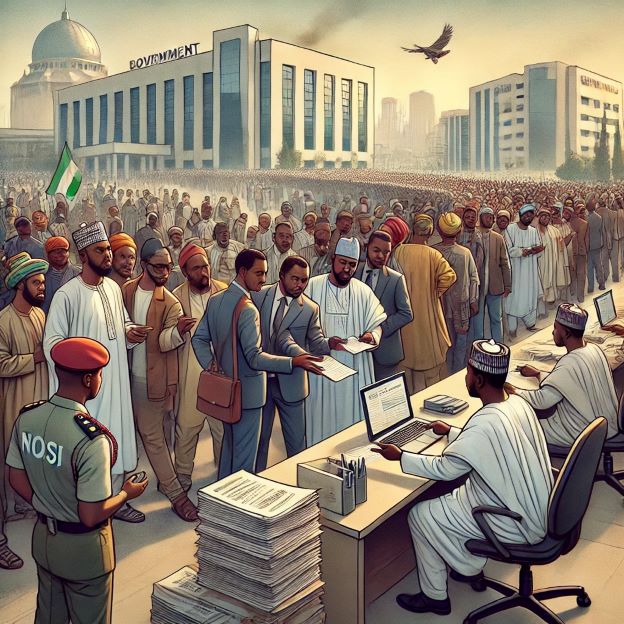

Improving tax compliance is clearly a priority for the current government, which introduced the Voluntary Assets and Income Declaration Scheme (VAIDS) to tackle the persistently low compliance rate. However, implementation has always been the problem. Numerous policies across various sectors have long been propagandized to no avail, and this may prove no different. Nigerians, in turn, need to be wary of what lies ahead. The country has never had a sound tax policy in recent times, meaning that Nigerians have never been effectively taxed. But with an increasing debt-to-GDP ratio (currently about 24%), debt accumulation has been proliferating. Although Nigerians always demand the utmost from their government, they also find the most resourceful ways to avoid paying taxes—be it legally or illegally, at both individual and corporate levels. From tampering with electricity meters to maneuvering their way into corporate tax exemptions, paying duties has never been in the Nigerian DNA.

With the current developments, however, taxation may become inevitable—although I still wouldn’t bet on it. Be that as it may, Nigerians should consider the idea of Ricardian equivalence, an economic concept that suggests unchanged demand in a debt-financed budget and increased savings in preparation for a rather preordained financial burden in the coming years. This would help them cope with the overwhelming obligations that could soon be upon them. As Max Schumacher from Network (1976 film) put it, “Taxes [are] suddenly a perceptible thing to us, with definable features.”

A country that did not blink at a statistical discrepancy allegedly worth billions of dollars—despite a history of conspicuous corruption and mismanagement—may well be a lost cause for economic redemption. The only hope lies in some form of collective incentive arising from tax accumulation and a sound fiscal policy.

Improving fiscal policy may be the only way to compel Nigerians to comply with taxation and become more aware of its importance. A ‘tax-me-I-task-you’ system—where sound tax policies are implemented, and citizens, in turn, demand accountability for how their hard-earned money is used—could foster trust. Furthermore, this would enhance the government’s ability to improve social mobility and income distribution, whether through wages, infrastructure, education, subsidies, or other means.

American research analysts Danilo Trisi and Isaac Shapiro published a report on the think tank website Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, detailing how government assistance has had a significant positive effect on child poverty in America. The report explains that while the share of children below the poverty line remained constant since 1970, it began to decline steadily when government assistance was included in the early 1990s. Another example is homelessness. The report outlines how government programs under the George W. Bush administration managed to reduce homelessness by about 30%. The Obama administration further extended these programs and introduced new ones, leading to continued nationwide reductions.

Taxes remain one of the most significant tools for achieving government goals in both developed and developing countries.

An excerpt from LSE’s Taxation for Developing Countries report by Ehtisham Ahmad and Nicholas Stern (1989) provides a quintessential representation of Nigeria’s tax system. The report states that economists Hinrichs and Musgrave, using international cross-section comparisons, stress that “the scarcity of simple ways of collecting revenue, or ‘tax handles,’ characterizes early stages of development.” Nigeria’s ongoing underdevelopment can be attributed to this very issue.

The highly successful Nordic model, practiced by Scandinavian countries, can be illustrated as “a triangle consisting of three interlocking factors,” according to Norwegian economist Sigrun Aasland. In an interview with American evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson, she explained that the so-called Nordic model first consists of “a strong tax-funded welfare state providing education, healthcare, and social safety nets. Second, an open market economy with active monetary and fiscal policies to ensure stability, distribution, and full employment. And third, strong collaboration in an organized labor market with coordinated wage formation and company-level cooperation.” The model, she continued, has demonstrated the ability to combine relatively high taxes with high productivity. She further explained how, in the past two years, nearly 30,000 people lost their jobs in the oil and gas sector due to falling oil prices and delays in productivity investments. Despite this, there was no social crisis or unrest, thanks to the workers’ social safety net—rather than job security—provided by the state.

Empirical evidence suggests that one of the most effective ways to improve public awareness and hold the government accountable is through adequate taxation. However, this is a give-and-take relationship that is often sabotaged by those who benefit from the status quo at both ends of the spectrum through passive dereliction.