Humans living in higher latitudes tend to have a variant of a gene involved in sensing cold temperatures, but it comes with a cost.

A human genetic variant in a gene involved in sensing cold temperatures became more common when early humans migrated out of Africa into colder climates between 20,000 and 30,000 years ago, a study published today (May 3) in PLOS Genetics shows.

The advantage conferred by this variant isn’t definitively known, but the researchers suspect that it influences the gene’s expression levels, which in turn affect the degree of cold sensation. The observed pattern of positive selection strongly indicates that the allele was beneficial, but that benefit had a tradeoff—bringing with it a higher risk of getting migraines.

“This paper is the latest in a series of papers showing that humans really have adapted to different environments after some of our ancestors migrated out of Africa,” explains evolutionary geneticist Rasmus Nieslen of the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the study. “There are a number of adaptations associated with moving into an arctic climate, but none with as clear a connection to cold as this one,” he adds.

Selection is optimizing fitness. It doesn’t optimize health, it doesn’t optimize happiness, so sometimes things are pushed by selection and they have negative side effects. —Johns Hawks,

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Although studies have demonstrated some striking examples of recent human adaptation, for instance, warding off infectious diseases such as malaria or having the ability to digest milk, relatively little was known about the evolutionary responses to fundamental features of the environment, namely, temperature and climate.

“Obviously, humans lived in Africa for a long time, and one of the main environmental factors that changed as humans migrated north was temperature,” explains population geneticist Aida Andres. So she and Felix Key the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig homed in on a gene, TRPM8, that encodes a cation channel in the neurons that innervate the skin. It is activated by cold temperatures and necessary for sensing cold and for thermoregulation. If there was a place to look for human adaptation, this gene looked like a good candidate.

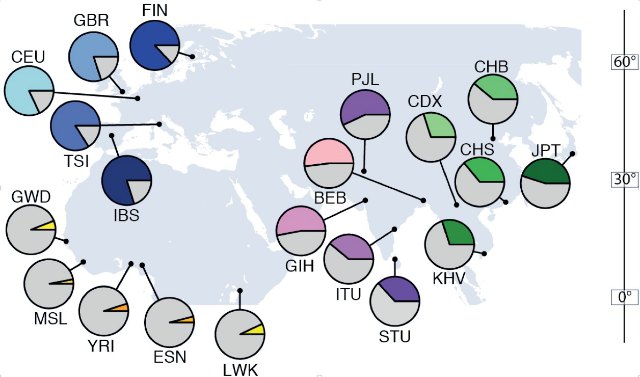

Using the 1000 Genomes dataset and the Simons Genome Diversity Panel, the researchers investigated variants of this gene in populations throughout Africa, Europe, and Asia. They found that a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in a regulatory region of the TRPM8 gene was “highly differentiated between different populations in the world,” Andres, now at University College London, says. And genotype correlated with latitude: 5 percent of people with Nigerian ancestry, versus 88 percent of people with Finnish ancestry, carry the cold-adapted variant.

Using models of population genetics, the researchers inferred that the cold-adapted allele had already existed in the ancestral African population, and that it became more common as people migrated northward. The geographic pattern was consistent with positive selection for the SNP at higher latitudes, Andres says.

“One of the interesting things about [this variant] is that it is relatively more common in Europe than in Asian people who live at the same latitude,” notes Hawks. “We don’t know why that should be. Maybe there’s a historical factor here that isn’t yet understood.”

To find out when selection on this variant occurred, the researchers looked for the SNP in the genomes from ancient remains of hunter gatherers or farmers that lived 3,000–8,000 years ago in Eurasia. It turned out that the allele was already common among these groups at least 3,000 years ago.

The connection between TRPM8 and migraine isn’t clear, other than the association. “Selection is optimizing fitness,” says anthropologist John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was not associated with the study. “It doesn’t optimize health, it doesn’t optimize happiness, so sometimes things are pushed by selection and they have negative side effects. This seems to be a case where a gene is pushed higher in frequency by selection for adaptation to cold, and it maybe has a bad side effect on increased susceptibility to migraines.” It’s also possible that the downside to having the cold-adaptive TRPM8 allele is a modern phenomenon, and that the migraine risk didn’t appear until more recently as environments have changed, says Nielsen.

F.M. Key et al., “Human local adaptation of the TRPM8 cold receptor along a latitudinal cline,” PLOS Genet, 14:e1007298, 2018.