Across several states in northern Nigeria, communities are besieged by relentless insecurity, marked by terrorist attacks and rampant banditry. These violent incidents have left 3.6 million people displaced, with thousands more homeless, children orphaned, and countless women and men spouseless. Beyond the physical devastation, an even more insidious affliction endures — the deep psychological scars borne by those who have lost loved ones, homes, and livelihoods.

While state governments strive to address the immediate needs of victims through rehabilitation, the silent suffering of many persists. Mental health professionals estimate that up to 60% of survivors (one out of every five displaced persons) experience symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) or depression. Despite this, mental health services remain grossly inadequate, with only a handful of facilities available to serve millions in need. Justina Asishana sheds light on the enduring trauma faced by those whose lives have been shattered by violence and the urgent need for comprehensive mental health support.

Insecurity in northern Nigeria has reached alarming levels, with over 3,000 reported cases of violent attacks in the last decade alone. The displaced population has swelled, with many forced to live in makeshift camps with little access to basic amenities. Amidst this chaos, the psychological toll on survivors is staggering.

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that in conflict-affected regions, one in five people experience mental health issues, a statistic that highlights the urgent need for intervention. However, the Nigerian government’s response has been largely focused on providing physical relief—food, shelter, and security—while the mental health crisis remains under-addressed.

Gladys Paul, a 35-year-old widow from Kurebe Village in Shiroro Local Government Area, speaks of the profound anguish that grips her heart.

“I will never forgive them,” she laments. “They made me lose my hardworking and loving husband, cutting him down while he tended to our farm. I held his cutlass-cut body in my arms as he breathed his last. Each mention of ‘bandits’ fills me with hatred. Forgiveness seems impossible.”

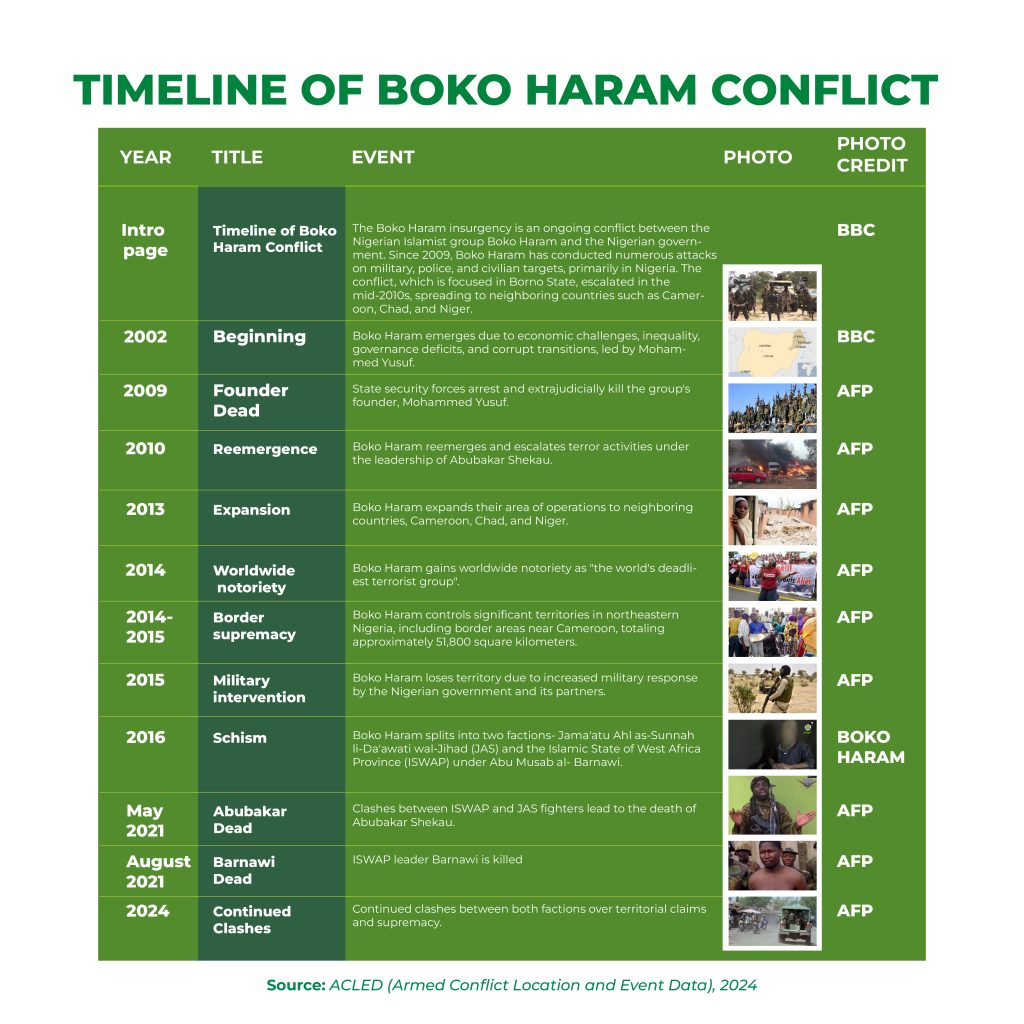

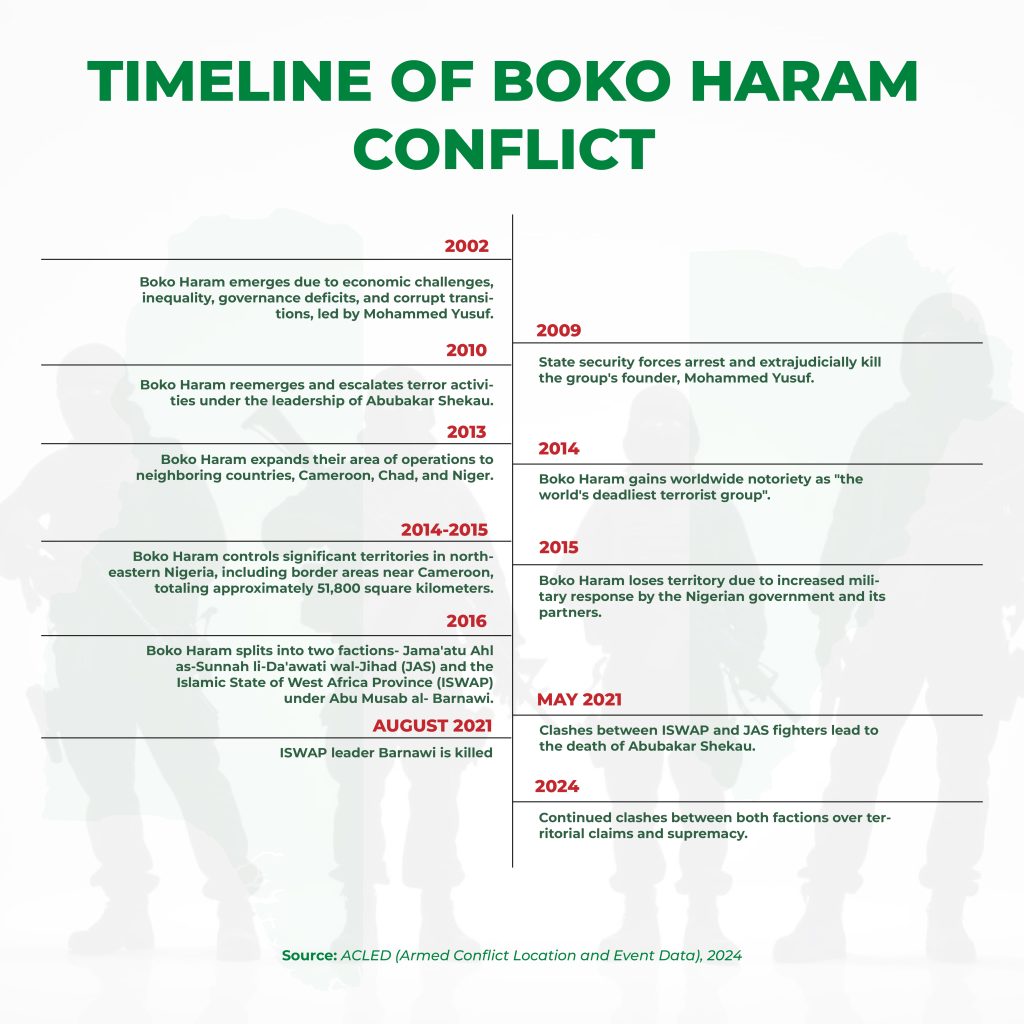

Ghumdia, now 24, recounts the horrific night when Boko Haram militants descended upon his family home in Maiduguri.

“At about 7:30 pm on the ill-fated day in Maiduguri, every family member was back home. All were in the living room, except Dad, who was relaxing outside on the veranda, when armed terrorists barged into our compound, forced everybody out and handcuffed every male.

“They carted away everything valuable in the house, including one of the two cars. After that, they used a machete to chop my two elder brothers and our father in the neck which led to his death. My brothers survived miraculously with medical intervention.

“Dad was gone! Yes on the spot! But it was difficult to accept the reality. Though traumatised, we were forced to relocate to a semi-urban centre, having been compelled to accept the inevitable. The breadwinner was no more, our health, education, and future—everything around the family’s interest seemed to be in jeopardy. The future looked bleak because our mother’s income could barely put food on the table. Our older brother had to defer his university education to take up a job to help support our mother.

“Three years later, in 2017, my mother was among ten police officers kidnapped by the same terror group, the Boko Haram. It felt like everyone, everything, including Providence was against my family. After seven agonising months, she was released back to us,” Ghumdia narrated, “The Boko Haram militants shattered our lives, threw our future into uncertainty and even after all these years, the trauma lingers.”

Rose Uriah’s voice trembles as she recalls the day in 2018 when her father fell victim to Fulani herders’ brutality. “It’s been years, but the pain remains raw,” she whispers, “I just cannot forget it. My father’s body was decapitated and packed into a wheelbarrow. Their act of barbarity robbed us of closure, denying my father a dignified farewell.”

Nigeria has 3.6 million people displaced by conflict and violence as of the end of 2022, out of which 1.9 million were living in protracted displacement in the north-eastern state of Borno.

Data shows Nigeria has the third highest number of displaced persons by conflict and violence in sub-Saharan Africa, coming after the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ethiopia.

Diverse Trajectories of Trauma

For some, like Edward Samuel and Yohanna Waziri, the trauma stems from the loss of property and security. They may not have lost loved ones but their trauma runs just as deep.

Samuel’s maize farm was his livelihood. It was set ablaze by marauding insurgents, “Those people, only God can forgive them. They set fire on my one hectare of maize farm that was due for harvesting. I had spent my entire investment to cultivate the crop. The destruction is something I cannot forget or forgive. My whole investment was destroyed,” Edward said.

Waziri lost one of his closest friends to bandits and was abducted the night before the burial. He was released a few days later. Amidst coping with these tragedies, he also lost N4 million to armed robbers. “I lost N4 million to armed robbers around that same period. At one point, it felt as if there was no God anymore. But somehow, by God’s grace, I could pull through,” Waziri said.

The Burden of Survival

For many survivors, the psychological scars run deep, affecting their ability to rebuild their lives. Women like Happy Shekwelo, Laraba Ezra, and Gloria Luka bear the weight of widowhood, left to fend for their children in the aftermath of violence. Forced to navigate the harsh realities of poverty and grief, they find themselves abandoned by a system ill-equipped to provide adequate support.

Happy Shekwelo from Kuchi in Munya Local Government Area of Niger State recounts the day bandits shot her husband on their farm in 2022. He was killed alongside other farmers. Fearing for her life in the face of frequent attacks, she fled to Minna with her two-year-old child, where she cleaned houses to make ends meet. After a while, she returned to Kuchi.

“We are back to Kuchi now because the security has improved a bit. I returned to my husband’s farm and began farming again, but it has not been easy taking care of myself and my child. I wish the state government would provide financial support to help us start a small business.”

Laraba Ezra, a mother of three, from Kafinkoro in Paikoro Local Government Area lost her husband in 2020. He was butchered with a cutlass while working on the farm. “My husband died three years ago and it has not been easy for me. He died as a result of banditry. Feeding and clothing my children is a constant struggle. My eldest child completed secondary school last year but has not gone to university because there is no money. There is no help coming from anywhere. I often go to my brother in Abuja to seek domestic work. I clean people’s houses and wash their clothes for a fee. Some pay me N20,000 monthly, while others pay me weekly.”

Gloria Luka was left with three children after her husband was killed by terrorists in Kuchi in Shiroro Local Government Area in December 2022. Without any farming skills, she turned to working at a local mining site, fetching sands and stone to sell to provide for her children. People buy the sand to sift in the hope of finding some gold or other precious stones.

NGOs as Beacons of Hope for the victims

Amidst this sea of suffering, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) have emerged as lifelines, addressing the often-overlooked psychological toll inflicted by violent acts.

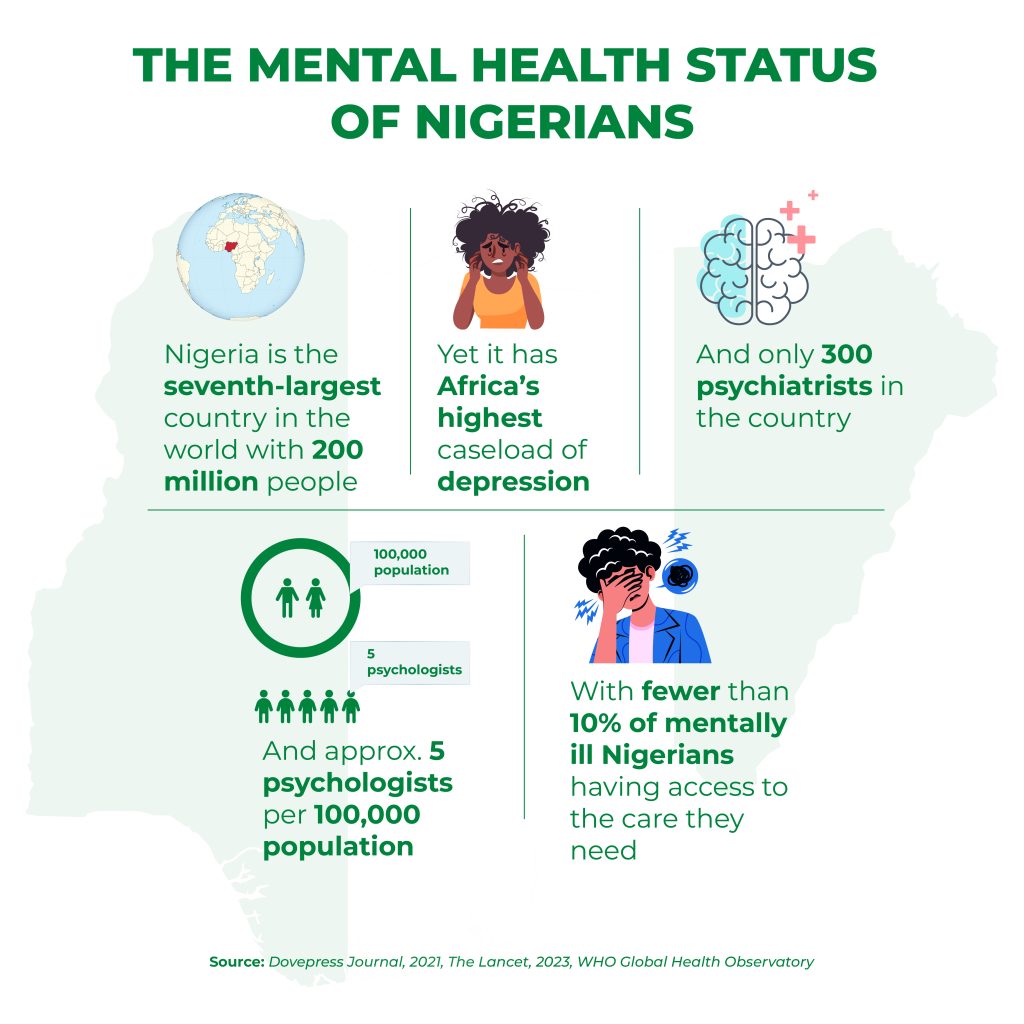

According to the WHO, Nigeria’s mental health services fall short of international standards, with a severe shortage of mental health professionals— ratio of 1 psychiatrist to 700,000 people nationally. As of 2020, Nigeria has a very limited number of psychologists available to address the mental health needs of its population. This starkly contrasts recommended global best practices, where comprehensive mental health support is integrated into emergency response frameworks.

Access to mental health services is uneven, with urban areas generally having better facilities and more professionals. For instance, Lagos State in the South-West has relatively better mental health facilities and professionals compared to other regions. However, the demand still far exceeds the available resources. Conversely, Borno State in the North-East, which is heavily affected by terrorism and conflict, has significant mental health needs but limited services.

Read Also: Tradition or health risk? Hot water baths after delivery linked to severe complications in women

MSF and other NGOs provide crucial support, but the infrastructure is insufficient to meet the high demand

Organisations like Médecins Sans Frontières, Christian Solidarity Worldwide Nigeria (CSWN) and the Catholic Diocese of Minna provide crucial support by offering psychosocial support, counselling, and trauma healing programmes that are culturally sensitive and tailored to the unique needs of those most affected by the violence.

These interventions include training community members as lay counsellors who can offer basic psychological support and identify cases that need professional attention. This approach ensures that support is accessible even in remote areas where professional mental health services are scarce.

One such initiative involves creating safe spaces within displaced persons camps where survivors can share their stories and receive peer support. These groups have been shown to reduce feelings of isolation and helplessness, fostering a sense of community resilience. Survivors who have benefitted from these programs often go on to become advocates for mental health, spreading awareness and reducing the stigma associated with seeking help.

These NGOs provide mental health professionals who offer coping strategies, emotional support, and trauma-informed care. CSWN has organised psychosocial support and training for those affected by insurgency in nine northern states which include Kaduna, Taraba, Benue, Plateau, Bauchi, Borno, Nasarawa, Niger and Adamawa states.

Nigeria’s mental health budget mainly financed through the central government health budget is about 3.3 to 4 percent of the total health budget. In 2024, the share of the total budget allocated to health is 4.66 per cent. In the last decade, this proportion was reached or exceeded in at least three other years – 2014, 2015 and 2023.

Mrs Agera Thelma Liti, the Chief Operating Officer (COO) of CSWN, emphasises the importance of holistic care: “Banditry doesn’t just destroy homes; it shatters lives. Our mission is to heal those wounds, rebuild resilience, and restore hope. Even though some have lost their spouses, family members, homes, and means of livelihood, we are trying to support them so they can be resilient and cope better with what they have gone through.”

Liti highlighted that reports from states where psychosocial support sessions have been held show that many victims have successfully used the skills they learned to overcome depression and feelings of helplessness. “The impact of these sessions is clear,” she said. “You can see it in the victims’ appearances when we visit them months later. They exude peace and serenity, and their confident demeanour reflects the absence of the fear and anxiety they once carried.”

Liti emphasised that the government needs to do more in this area, as funding limitations prevent reaching more victims. “The government must look beyond just providing food. When someone loses a family member or a community is attacked, there’s much more support required. While distributing food, toiletries, and emergency relief materials is important, it’s not always enough. Often, these people are so traumatised that eating isn’t a priority. Without psychosocial support, they can’t fully move on from their past pains and hurts or live freely.”

The Need for Government Action

While NGOs play a crucial role, scaling these interventions to meet the vast news of northern Nigeria requires government involvement. Recent efforts have shown that government-NGO partnerships can be a powerful force for change. For instance, in Borno State, a pilot program supported by the Ministry of Health and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) has successfully integrated mental health services into primary healthcare centres. This model, which trains general healthcare workers in basic mental health care, has proven effective in reaching a larger population and could be expanded nationwide.

Innovative approaches to trauma healing are also making a difference. For example, in Maiduguri, a mobile mental health clinic was introduced to reach survivors in hard-to-access areas. The clinic, which travels to different communities each week, provides counselling, psychiatric services, and follow-up care. This initiative has been particularly successful in reaching women and children who are often the most vulnerable to psychological distress.

Rev. Father Dauda Musa Bahago of the Catholic Diocese of Minna underscores the urgency of addressing mental health needs. “We must provide more than just food. Trauma healing is essential for rebuilding shattered lives.”

He urged the Niger State Government to include counselling and therapy as part of the humanitarian assistance for victims of banditry and terrorism, rather than focusing solely on food provision.

While these efforts are commendable, they must be part of a larger, coordinated strategy to address the mental health crisis in northern Nigeria. Experts stress the need for a national mental health policy that prioritises trauma healing as part of the broader humanitarian response. This policy should include provisions for training mental health professionals, integrating mental health services into all levels of healthcare, and ensuring that mental health care is culturally appropriate and accessible to all.

Security experts and mental health professionals are caught in a difficult situation—where providing crucial psychological support in conflict zones is hampered by the very violence they seek to alleviate. As Minna-based psychologist Pamela Israel points out, the uncertainty of attacks often forces counsellors to stay away from these areas, leaving victims without the care they desperately need. Ignoring this mental health crisis only risks perpetuating the cycle of violence and instability in the region.

As Nigeria grapples with the complexities of conflict resolution, mental health support must be prioritised to ensure that no one is left to navigate the dark corridors of trauma alone. The government must expand its focus beyond immediate relief to include comprehensive mental health care, ensuring a holistic approach to health and recovery,

(This article was produced with the support of the Africa Women’s Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) with support from the ONE Campaign)