With the number of new mpox cases continuing to rise, and many more potentially undetected, African countries affected by the latest outbreak are racing to mobilize funds and urgently deploy medical countermeasures, including vaccines. But as the current epidemic unfolds, there is an undeniable feeling of déjà vu. Global efforts are falling short of what is needed to mount an urgent, well-coordinated response to curtail the crisis.

The world learned several lessons from COVID-19. But barring some areas of incremental progress, these lessons have yet to be translated into concrete actions.

Below we look at the global response to the latest mpox outbreak to date, zooming in on three specific dimensions that pose the key challenges. These include: the dynamics of the emergency declarations issued by WHO and African Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC); the incremental progress of surge financing; and the slow and fragmented start to procurement and delivery of medical countermeasures.

Emergency declaration – empowered regional decision-making, but continuing issues with WHO’s ‘binary’ approach

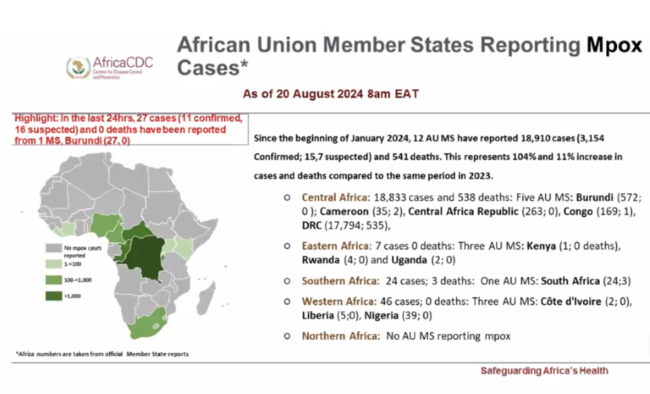

On August 13, the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) officially declared the ongoing mpox outbreak a Public Health Emergency of Continental Security (PHECS). This was the first time a regional institution had made such a declaration, marking a significant milestone in the empowerment of African institutions to lead and coordinate responses to public health threats.

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) declaration of a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) followed the next day. The decision, meant as a signal to donors to step up resources to curtail an outbreak, was made earlier than in previous outbreaks. In comparison, during the 2022 mpox outbreak, the declaration came after approximately 16,000 cases were reported across 75 countries. In contrast, the 2024 declaration was made before the virus had spread beyond Africa, signaling a more proactive approach.

While the regional and global declarations were aligned in this case, questions remain about what happens if decisions do not sync up.

This underlines the ongoing need to improve the WHO “trigger” mechanism for a PHEIC. It needs to shift from a binary approach [global declaration vs. no declaration at all] to a tiered system reflecting the severity of a pathogenic outbreak, along an ‘epidemic scale‘ like hurricane or earthquake scales, which can serve as a more nuanced trigger for different types of responses.

Surge financing: incremental progress but not yet fully operational

The need for adequate surge or at-risk financing is arguably one of the most salient lessons from COVID-19. G7 and G20 leaders have recognized its importance and several funds and initiatives, including various Development Finance Institutions and the Africa Epidemics Fund, have signaled support, yet there is still little, if no, money flowing.

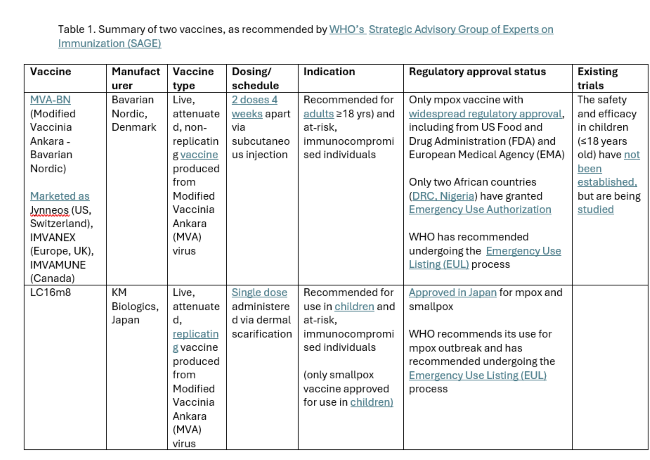

Gavi’s $500 million First Response Fund that makes resources immediately available for outbreak response is an exception. The Fund was approved by its board in June 2024, so Gavi could theoretically start drawing on these resources. However, these funds can only be used for vaccines, not other medical countermeasures, and regulatory barriers are creating hurdles. The mechanism can only procure vaccines that have received WHO emergency use listing, even though two available mpox vaccines (MVA-BN and LC16m8) have already been approved by several well-resourced regulatory authorities.

In the short term, Gavi and other global health initiatives should revise procurement policies to recognize approvals from WHO-Listed Authorities—a new framework established by WHO to identify mature regulatory bodies operating at an advanced level of performance.

Surge financing should also be deployed to contract for manufacturing capacity. Specifically, Denmark’s Bavarian Nordic and Japan’s KM Biologics that produce the two mpox vaccines recommended by WHO could use third party facilities to ramp up production.

The current outbreak underscores the need for donors to continue to work towards a more coordinated and coherent surge financing facility covering a range of health products and uses (this could entail building upon existing mechanisms rather than creating new ones).

Vaccine procurement: slow and fragmented response so far

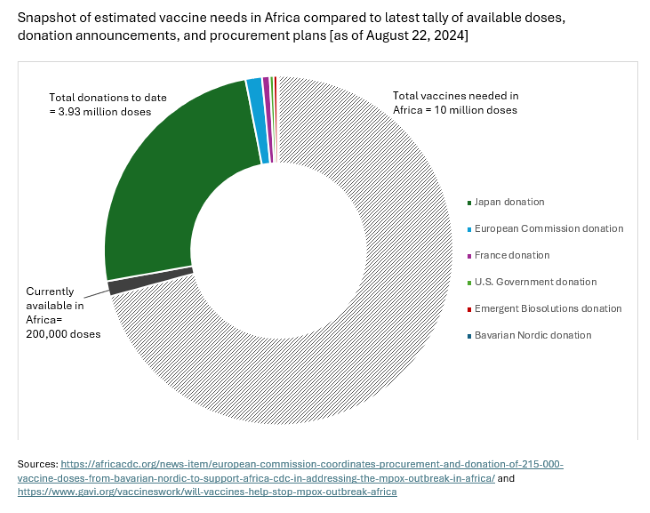

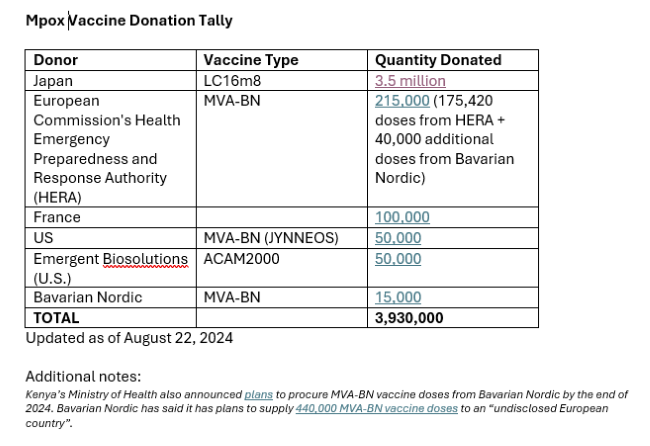

We already have safe, efficacious vaccines to prevent mpox. But at roughly $100 a shot for Bavarian Nordic’s two-dose regimen (MVA-BN), the vaccine that has been the most widely used in Europe and the Americas, mpox vaccines are expensive for Africa. The immediate priority should be getting as many of the 10 million vaccine doses needed, as estimated by the Africa CDC, procured and delivered to affected countries at the epicenter of the outbreak.

Donated doses can help fill immediate gaps. The DRC whose regulator recently granted emergency use for two vaccines now expects to receive some 315,000 donated MVA-BN doses from the European Union and the United States – with doses from the United States reportedly due to arrive early as next week. Additional announcements are trickling in – with a reported 3.5 million donation by Japan of its one-dose LC-16 vaccine, produced by KM Biologics and approved for use in children, as a significant step forward.

Now is the time for other countries holding mpox vaccine stockpiles to step up, and share supply with the most affected countries – so as to curtail further spread.

But dose donations will require extremely close coordination to manage the myriad legal, regulatory, logistical barriers involved. In leading this effort, Africa CDC should partner with Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, drawing on its experiences coordinating COVID vaccine donations.

Last week, Bavarian Nordic indicated it has capacity to manufacture 10 million doses by the end of 2025, including up to 2 million doses by end 2024. Activating pooled procurement mechanisms, backed by financing from donors alongside African regional entities and countries, to coordinate purchasing should be a critical component of the global effort.

Bavarian Nordic has also reportedly entered into an agreement to transfer vaccine manufacturing technology to selected African manufacturers, according to Africa CDC Director Jean Kaseya, speaking at a press briefing just this week. While this would be an important move, announcements around diversifying manufacturing via technology transfer agreements will not produce the doses needed in time to curtail the current outbreak.

Delivery of countermeasures challenged by conflict, logistics and health systems issues

Delivery of medical countermeasures was another shortcoming of the COVID response. Specifics of the current outbreak pose particular challenges for delivery: transmission mechanisms and target populations differ from previous mpox outbreaks; there is ongoing conflict in the most affected areas, such as eastern DRC; and vaccines must either delivered in multiple doses [MVA-BN] or in the case of the the Japanese-made LC16 vaccine, using an intradermal method of administration that a lot of vaccinators are not familiar with.

Global health institutions, including Gavi, UNICEF, and WHO, also need to work closely with other partners, including humanitarian organizations and multilateral development banks, like the World Bank, to leverage their financing to support delivery and related response needs.

Major Research and Development needs

Finally, there are additional R&D needs. Usage of Bavarian Nordic’s MVA-BN vaccine is currently limited to adults, underscoring the urgency to broaden usage to children and adolescents, who are disproportionately affected by the current outbreak. In addition to vaccines, R&D is needed for rapid, point-of-care diagnostics and treatments.

While these immediate priorities should be top-of-mind, longer-term efforts can help down the line. Gavi’s new Vaccine Investment Strategy, approved by its board in June 2024, includes plans to set up a global stockpile.

World leaders must respond to the calls for strong coordination and immediate access to medical countermeasures. If not, the evaluations and after-action reviews of the international response to this latest mpox outbreak will read as the same story of inequitable access that characterized the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keller is a Policy Fellow and Deputy Director of the Global Health Policy program, Center for Global Development and Guzman is a Senior Policy Fellow and Director of the Global Health Policy program, Center for Global Development.

![[INSIDE VIEW] The Global Response to Mpox: A Feeling of Déjà Vu? By Janeen Keller and Javier Guzman Scientist runs a test on the mpox virus as part of a Nigerian-United Kingdom research collaboration.](https://ashenewsdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Scientist-runs-a-test-on-the-mpox-virus-as-part-of-a-Nigerian-United-Kingdom-research-collaboration-e1757268281546.jpg)