On paper, the Nigerian agricultural sector is swimming in cash. In the corridors of the National Assembly and the sleek PowerPoint presentations of the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, the narrative is one of “massive production” and “restoration.”

Yet, in the dusty markets of Minna, the overflowing grain silos of Kano, and the farm settlements of Benue, the reality is starkly different. Despite the Federal Government increasing the agriculture budget in recent years, the average Nigerian is paying more for food today than at any point in recent history.

As we settle into 2026, a critical question hangs over the President Tinubu administration: Why is increased funding failing to translate into food security?

The Maputo Math: A broken promise

President Bola Tinubu’s “Budget of Restoration” for 2025 was hailed as a turning point. The nominal increase in allocation was historic. However, analysts at ASHENEWS have crunched the numbers, and the “boom” appears to be a mirage when adjusted for inflation and international benchmarks.

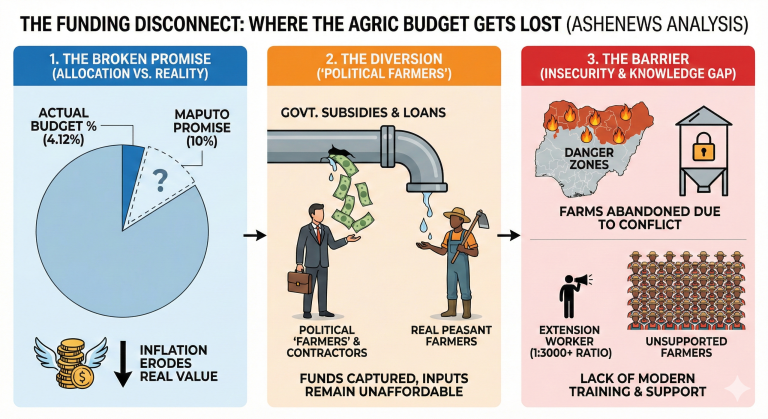

While the ₦2.27 trillion figure looks impressive, it constitutes only about 4.12 per cent of the total national budget. This is a far cry from the 10 per cent commitment made under the Maputo Declaration, a pact Nigeria signed nearly two decades ago to ensure food sufficiency.

”We are celebrating motion, not movement,” says Dr. Chike Obi, an agro-economist based in Lagos. “When you factor in the devaluation of the Naira, the real purchasing power of that budget for imported machinery, fertilizers, and chemicals is actually lower than it was five years ago. We are throwing Naira at a Dollar problem.”

The “political farmer” syndrome

Perhaps the most damning disconnect lies in who actually gets the money.

The All Farmers Association of Nigeria (AFAN) has raised the alarm repeatedly last year. In a scathing critique, AFAN leadership noted that government interventions, such as the National Agricultural Growth Scheme (NAGS-AP), often bypass the peasant farmers who produce 80 per cent of Nigeria’s food.

”Real farmers are in the bush, battling kidnappers and high input costs,” said a state chapter chairman of AFAN who pleaded anonymity.

“The people you see collecting subsidized fertilizers and cheap loans in Abuja are ‘portfolio farmers’, politicians and contractors who own farms on paper but have never held a hoe. They collect the funds, round-trip the money, and the real farmer buys fertilizer at the open market rate of ₦45,000 per bag.”

This “capture” of funds means that despite trillions released, the input cost for the actual producer remains sky-high.

Silos of insecurity

Funding becomes irrelevant if the farm itself is a death trap. Between 2023 and 2025, insecurity in Nigeria’s food baskets, Niger, Borno, Kaduna, and Benue, has forced thousands of farmers to abandon their harvest.

The 2025 Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan projected that over 30 million Nigerians would face acute food insecurity by mid-2025. The prediction has largely held true.

In Niger State, mining disasters and banditry have shrunk arable land usage. In the North East, insurgents still dictate who plants and who harvests.

The budget allocates billions to “mechanization” and “clearing of land,” but it allocates little to the specific security architecture needed to protect those lands.

The extension void

Another critical failure point is the near-extinction of the Agricultural Extension Worker. Global best practices suggest a ratio of 1 extension worker to 800 farmers.

In Nigeria, the ratio is estimated to be 1 to 3,000 or worse. The 2025 budget heavy-lifting is on capital projects like the procurement of tractors and building of silos which are lucrative for contractors.

However, “soft” investments like hiring and training extension officers to teach farmers about climate-resilient seeds or modern pest control are woefully underfunded. The result is a farming population practicing 19th-century agriculture in a 21st-century climate crisis.

The verdict

As 2026 unfolds, the Tinubu administration stands at a crossroads. The government has successfully cleared the first hurdle: admitting that the sector needs more money. But money alone is not strategy.

To move from ” Budget of Consolidation, Renewed Resilience and Shared Prosperity” to “Plates of Plenty,” three things must happen immediately:

- De-politicize Distribution: Use technology (biometrics/NIN) to bypass the “political farmers” and route subsidies directly to rural wallets.

- Secure the Farms: Agro-Rangers must be more than a ceremonial force; they need to be deployed offensively to clear farming corridors.

- Monitor Execution: The Ministry of Agriculture must publish quarterly, verifiable reports on outcomes (tonnes produced), not just outputs (money spent).

Until then, the trillions in the budget remain just ink on paper, while the price of a measure of garri continues to defy gravity.