On the surface, the disastrous flooding that overwhelmed Maiduguri in northeastern Nigeria was caused by a ruptured Alau dam. HumAngle found that the dam has suffered years of devastating decay, despite multimillion funds disbursed for its rehabilitation.

By Ibrahim Adeyemi, Mansir Muhammed, Alamin Umar, Usman Abba Zanna

When flooding submerged towns and villages of Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state in North East Nigeria, a wave of terror gripped the atmosphere. Thousands of houses were buried underwater; the heavy rainfall swallowed people as families lost track of one another. Hundreds of residents lost their homes to the visiting floods taking over the city.

Goni Usman, a survivor of the fierce flooding, is desperately searching for his wife and five children after violent floods took his family away from him. “I am finished,” he sobbed bitterly as he spoke to rescue workers at one of the displacement camps in the town. “We went to the Babagana Wakil Camp but couldn’t find them. I saw some of my neighbours there, but I couldn’t find my family.”

A despondent Goni isn’t alone in this trouble. Though residents say the actual figures are much higher, authorities say about 30 persons were killed by the flooding, over 400, 000 residents were displaced and around one million people were generally affected, according to the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA). The terror that turned troubled Maiduguri into a Mississippi of tears was, however, not orchestrated this time by the known insurgents and violent extremists terrorising northeastern Nigeria.

The official narrative provided by NEMA was that nearly half of Maiduguri was buried in disastrous flooding after the Alau Dam, a critical infrastructure designed to regulate water flow and provide irrigation and drinking water, overflowed following heavy rainfall. In no time, floodwaters swept through over 23, 000 neighbourhoods, drowning the city under its force.

When the disastrous flood struck, the State Governor, Babagana Zulum, addressed the people through the media, expressing commitment to building infrastructures to avert future floods. “We shall leverage on this calamity as an opportunity to invest in sustainable practices and infrastructure that can withstand the forces of nature,” he pledged, asking locals to cooperate with authorities over his fresh vow. “I invite and encourage other stakeholders to collaborate with our agencies to identify the best ways of assisting. Together, we can create a robust response plan that would address not only immediate needs but also long-term recovery and rebuilding efforts.”

The statement seems appealing to the Borno public, but the Alau Dam collapse was bound to happen, only that authorities had turned deaf ears to prior warnings from environmentalists in and around the region. According to the experts, there had been cracks in the dam’s walls, and erosion had taken over the embankments, a result of years of abandonment that weakened its structure.

A few days before the flooding uproar, dozens of residents living near the dam were asked to leave for fear of impending hazards that may result from the overflowing dam. Forewarned again by residents and concerned people of Borno, the government insisted that the state was not under any flooding threats, claiming to have done some independent assessment of the dam.

A HumAngle investigation has, however, revealed a case of negligence on the side of the state government and mismanagement of funds by officials of concerned ministries. Behind this neglect is a broader pattern of mismanagement that plagues infrastructure projects across Nigeria. The Alau Dam is not an exception. Funds disbursed for the dam’s maintenance were misappropriated, with little to no accountability. Now, the people of Maiduguri are paying the price for the systemic rot.

Evidence of neglect

ALSO READ [VIEWPOINT] Maiduguri Flood: God’s Wrath Or Human Greed?

A HumAngle satellite analysis of the dam’s location reveals that two gates control the flow of water out of Lake Alau. For nearly two years, only one of the dams has been functional. Satellite evidence shows that the dam on the western side of the lake has been destroyed since October 2022, with the surface destroyed beyond recognition.

We obtained and collated satellite images showing the decaying journey of the dam in the past years.

August 2022: The last known imagery of the dam is intact, according to available data.

October 2022: Satellite images show water violently and uncontrollably overflowing the damaged structure. The dam was likely destroyed sometime between August and October 2022.

November 2022: This imagery reveals the extent of the damage to the dam, with more than 50 per cent of the structure wrecked beyond recognition.

February 2023: The latest available imagery of the lake shows the dam remains in disrepair, with no signs of restoration. This condition persisted until the recent flooding earlier this week.

Mismanagement of funds?

The federal government again raised people’s hope after the flooding, with a pledge to “upgrade” the Alau dam to avoid future flooding. HumAngle, however, finds that funds running into hundreds of millions had been disbursed for the rehabilitation of the dam, but were either mismanaged or misappropriated.

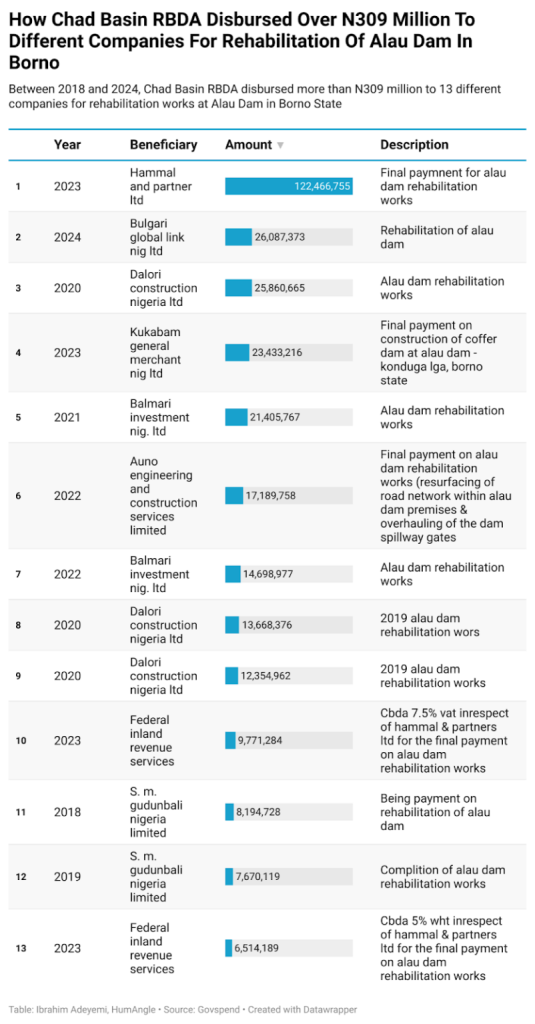

According to Govspend, a public portal dedicated to tracking the federal government’s spending, more than ₦309 million (309,316,169.01) were disbursed for rehabilitating the Alau dam between 2018 and 2024. The funds were released in 13 tranches by the Chad Basin River Development Authority (CBDA) to different companies.

In 2020, one of the companies, Dalori Construction Nigeria Ltd, received ₦51.7 million in three months — ₦13.6 million in March, ₦12.3 million in April and ₦25.8 million in June. S.M Gudunbali Nigeria Ltd, another company, was paid ₦8 million in 2018 and N7.6 million the following year.

Similarly, Balmari Investment Nigeria Ltd was paid ₦14.6 million in 2022 and ₦21.4 million a year before. On November 12, 2022, Auno Engineering and Construction Services Ltd, was paid ₦17 million for rehabilitation works on the dam. In June 2023, Kukabam General Merchant Niger Ltd was paid ₦23.4 million for the same purpose. On September 20, 2023, the agency disbursed more than ₦16.2 million to Federal Inland Revenue for “VAT in respect of Hammal and Partners Ltd for the final payment on Alau dam.”

Hammal and Partners Ltd received the highest amount of money for the same project other companies were paid for. It received ₦122.4 million in 2023 alone. However, on July 29, 2024, the agency also paid ₦26 million to Bulgari Global Link Nigeria Ltd for rehabilitation work on the Alau dam.

Curiously, in the name of “rehabilitation”, the agency has disbursed funds to different companies in the past five years. HumAngle’s satellite investigation, however, shows a pattern of abandonment, causing a damning decay of the Alau Dam infrastructure, which later caused flooding that almost swallowed the entire capital city.

When HumAngle contacted the Managing Director of the CBDA, Abba Garba, for comments concerning the disbursement of the funds and repair of the dam, he said, “We are at the airport, about receiving the minister. Let’s talk later,” We have not been able to reach him since then.

“Last year and the year before it, communities around the dam were flooded. And despite several warnings, I don’t know why the government refused to take preventive measures. There was research from the University of Maiduguri that established the condition of the dam. Assuming the government had taken preventive measures and repaired the dam, it would have saved us a lot of resources, human lives and properties,” said Ibrahim Izge, an environmental activist in Maiduguri.

Devastating effects

The construction of the Alau Dam started in August 1984 and completed in 1986. Located in the Alau community of Konduga Local Government Area, the dam gets water supply from the Ngadda River in the Gwange community of Maiduguri, serving the primary goal of providing water for irrigation, domestic use, and fisheries developments. The dam has played a vital role in sustaining the livelihoods of local farmers, enabling them to grow crops in a region otherwise prone to drought and desertification.

However, demands on the dam would later increase as the population grew and urbanisation intensified. What had once been a source of life and prosperity gradually became an overburdened structure, requiring constant attention and maintenance to keep it functional. As with many public infrastructures in Nigeria, the Alau Dam became a victim of administrative neglect, lack of political will, and insufficient funding, experts said.

The collapse of the dam also has significant economic and social consequences. Farmers relying on the dam’s water for irrigation have lost not just their crops but also their means of survival. The fertile land that once surrounded the reservoir is now inundated, and the next planting season is uncertain. Agricultural losses are estimated to run into billions of naira, significantly affecting an economy that was already struggling with the effects of climate change and conflict.

Businesses in Maiduguri that depended on the dam for their water supply have also been severely impacted. The water shortages that followed the collapse have disrupted daily life, with many residents forced to seek alternative, often unsafe, sources of water. The collapse has intensified water scarcity, exacerbating the region’s public health crises as people now face a higher risk of waterborne diseases like cholera and typhoid.

The human toll of the Alau Dam collapse has been enormous. Displacement camps earlier shut down by authorities were reopened to accommodate the flood victims. For many, the flood was a cruel irony: After surviving years of conflict, they now face another existential threat from nature. In the overcrowded displacement camps, access to food, water, and healthcare is woefully inadequate, heightening the risk of malnutrition and diseases.

This report was produced in partnership with the MacArthur Foundation under the ‘Promoting Transparency in Insurgency-Related Funding in Northeast Nigeria’ Project.