In recent years, Africa’s security landscape has become increasingly shaped not just by armed groups, political upheavals, and foreign interventions, but by a less visible weapon: disinformation. From violent extremists to state actors and even criminal gangs, disinformation has been deployed as a strategic tool to win sympathy, obscure failures, and manipulate perceptions. Its impact is proving just as dangerous as guns and bombs.

Extremists, preachers, and the digital battlefield

Violent extremist organizations across Africa, particularly in the Sahel, have mastered the use of disinformation. They exploit religious narratives and cleverly crafted identities to present themselves as defenders of marginalized communities. In gold-mining regions, for example, extremist groups deploy preachers who cast them as protectors of artisanal miners against state neglect.

These narratives are amplified through social media networks, where ordinary people—often unaware they are spreading falsehoods—help extend the reach of extremist propaganda. By misusing parochial interpretations of religious texts and cloaking themselves in deceptive language, extremist groups steadily build a façade of legitimacy that enables them to recruit, fundraise, and secure local collaborators.

Governments and the politics of disinformation

But it is not only extremist groups that use this tactic. Governments—both elected and unelected—have also adopted sophisticated disinformation strategies. In many cases, they use it to distract attention from pressing socioeconomic crises such as unemployment, corruption, and insecurity.

By shaping narratives and silencing fact-checkers, these states not only suppress dissent but also undermine accountability. In the Information Age, when citizens have greater access to alternative sources of news, the consequences of such state-led disinformation are more corrosive than ever. It fosters irresponsibility at the highest levels and further erodes public trust in governance.

Military juntas, Wagner, and manufactured victories

The resurgence of military governments since 2021 has added another dimension to the disinformation problem. Military juntas in countries like Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have justified their rule with claims of restoring stability and fighting terrorism, yet many of their strategies have proven counterproductive.

I have long warned about the dangerous collaboration between these regimes and Russian private military contractors such as Wagner. For years, disinformation painted Wagner as a decisive force in counterterrorism. In reality, recent revelations—including Malian forces accusing Wagner of incompetence—show that many of the so-called “successes” were manufactured propaganda.

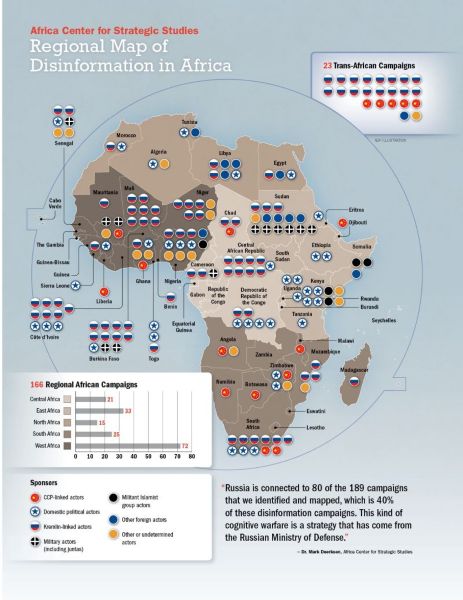

The result is stark: today, the Sahel stands as the epicenter of global terrorism. Worse still, educated Africans and non-Africans alike fell for the Wagner narrative, mistaking disinformation for truth and embracing anti-imperialist rhetoric that only deepened insecurity. Foreign powers, too, continue to exploit disinformation to advance their geopolitical interests in Africa, making the region a playground for dangerous narratives.

Bandits and the new face of criminal propaganda

Disinformation is no longer the preserve of extremists and governments. Even criminal groups such as bandits have started to deploy it. Recently, one group demanded the construction of schools and hospitals in exchange for halting their attacks. On the surface, such demands seem rooted in legitimate socioeconomic grievances. But in reality, they represent a new frontier in criminal propaganda—an attempt to gain public sympathy and legitimacy while continuing acts of violence.

A battle beyond the battlefield

The rise of disinformation in Africa’s security crises reveals a troubling truth: the fight for stability is no longer confined to physical battlefields. It is being waged in minds, narratives, and digital spaces. Extremists exploit faith and frustration, governments manipulate stories to protect their power, and criminals reinvent themselves as champions of social causes.

Disinformation has become both a weapon and a shield. Until African societies, institutions, and partners confront this reality, the region will continue to be haunted not just by insecurity, but by the powerful lies that sustain it.

Owusu is an International Relations and Security Analyst and Geopolitics wtiter