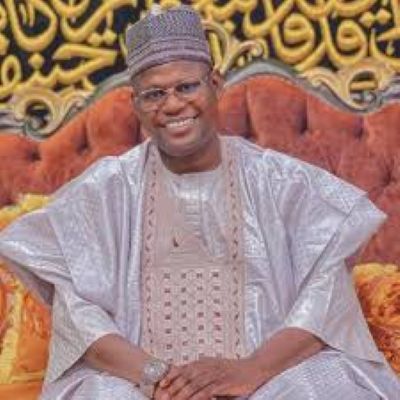

There is an ongoing and increasingly heated discussion around the teachings and methods of Sheikh Yahya Ibrahim Masussuka. His bold interpretations and open challenges to mainstream clerical authority have unsettled many, yet they also speak to a deeper cultural moment in Northern Nigeria. This is not merely a theological dispute but part of a larger reckoning with decades of unchallenged dogma and intellectual conformity.

Masussuka’s emergence and the fierce reactions to him, expose a region caught between inherited certainty and the demands of critical thought in a changing world.

These debates may sound chaotic, but they signal renewal. The North is beginning to think again, publicly, sometimes clumsily, but without fear.

Development without introspection will always be fragile. The region needs a cultural summit, not only an economic one: a deliberate conversation about the values, hierarchies, and silences that have shaped it for half a century.

Over the week, I looked through several Facebook posts and commentaries from both supporters and critics of Masussuka. Many of them written by writers like Aliyu Dahiru Aliyu, Mohammad DonHussy, Dattijo Kabir Muh’d Raji Bello etc, inspired this reflection. They reveal a society wrestling with its conscience, trying to define where faith ends and freedom begins. These informal digital conversations mark a turning point: they show that the North is no longer afraid to think aloud.

At this moment, Nigerian Christians would also do well to pay attention. This debate within Islam offers rare insight into the intellectual and spiritual tensions that shape our shared society. Understanding these nuances can help bridge divides and clarify the social undercurrents that have, at times, produced violent offshoots like Boko Haram, or fed into the tragic narratives of targeted killings of Christians reported in recent weeks. Building empathy across faiths begins with understanding how ideas evolve within them. The more each community comprehends the other’s internal debates, the stronger the nation’s moral fabric becomes.

Masussuka’s method and the failure of engagement

One thing remarkable about Masussuka is how deliberately he avoids personal attacks. Even when he describes his opponents with symbolic phrases such as “robe-wearing bearded he-goat” or “the lying spider,” he never names them.

At other times, he deploys local metaphors like “uban daba” (the ring leader) or “girma ya riga wayo” (big for nothing)-mocking, yes, but framed in cultural idiom rather than direct insult. He critiques ideas rather than individuals, using vivid metaphors that clarify without defaming. His language is carefully measured, avoiding the legal and rhetorical traps that could easily be used against him.

At any rate, these remarks are often responses to uncharitable descriptions of him by those same people. Several clerics have consistently called him “Kala Kato”, a label meant as an insult but loaded with irony. The phrase itself in Hausa means “according to some man,” derived from the Arabic “qala” (he said or according to)-the very structure of Hadith narration.

To accuse a man who questions the authenticity and multiplicity of Hadiths of being Kala Kato, a term literally built on the very chain of sayings he critiques, is self-defeating. It shows how language, when used carelessly, can betray the ignorance of those who wield it.

A certain Salafi preacher once referred to him as “gardi,” a term often used derisively in popular discourse. Masussuka’s response was both witty and erudite. He explained that “gardi” likely derives from the Arabic word “garada”, which means “to chirp or sing melodiously,” as birds do-root also associated with rhythmic or musical recitation of the Qur’an. He said that being called gardi was no insult but a compliment, for it describes one who recites with beauty. With that single explanation, he turned a slur into a lesson and exposed the linguistic ignorance behind it.

That is Masussuka’s style: poised, precise, and pedagogical. He fights polemics with philology, transforms insult into instruction, and shows that clarity can be a more potent weapon than rage. Such discipline and restraint deserve acknowledgement, even from those who disagree with him.

His central argument, that faith must align with the Qur’anic principle of “no compulsion in religion”, strikes at the heart of contemporary contradictions. His detractors call it heresy, yet his followers see the coherence they have long sought from religion in it.

His rise fills the vacuum left by decades of clerical rigidity. For years, engagement gave way to performance; debate to denunciation. Sermons became spectacles, and moral certainty replaced intellectual humility. Masussuka challenges that, not with fury but with logic—and that, for many, is precisely why he resonates.

Ironically, attempts to suppress him have only magnified his reach. The much-publicized Kaduna meeting of clerics, convened to condemn his views and issue warnings against him, ended up serving as his most effective promotion. What was meant as a show of unity against “deviance” instead revealed insecurity, inadvertently drawing wider public attention to his ideas. In the digital age, outrage is oxygen. The meeting amplified the very voice it sought to silence.

Still, the question is not why he speaks, but why others have failed to speak with equal clarity. When faith grows so brittle that dissent feels like danger, something sacred has already been lost.

The ability to debate without fear is the foundation of faith. Theologians once argued passionately yet respectfully; today, questioning is often treated as rebellion. Masussuka’s emergence reopens that space. As Marzuq Ungogo notes, disagreement should not become arrogance. People reason from different frameworks; dialogue begins with understanding, not accusation.

For four decades, reformist preaching in the North began as renewal but hardened into exclusion. It blurred the lines between piety and politics and left little room for nuance.

The result is a society where disagreement is equated with disbelief, and where a growing number of young people now casually label those who hold different views -even scholars or elders -as jahilai, ignorant or misguided in religion. What passes for orthodoxy often functions as social control sustained by fear and repetition.

Ibrahim Musa observes that Masussuka’s influence lies in communication, not conspiracy. His clarity, timing, and digital reach made him effective, while attempts to silence him only amplified his voice. In the algorithmic age, censorship is publicity. What we need is a reasoned response, not a reaction. Musa’s conclusion is simple: coercion no longer works; tolerance and wisdom must.

The danger of knowledge, gatekeeping, and the politics of hypocrisy

Ahmad Sadiq argues that the real issue is control of knowledge. “‘Leave it to the experts,’” he writes, “is how societies kill innovation.” Knowledge should enlighten, not exclude. Masussuka’s defiance challenges the idea that thinking is a privilege of the ordained. To democratize learning is not insulting scholars but reminding them that wisdom grows when shared.

As Usman Isyaku puts it, “The day I realised that clerics are humans and none of them receives revelation, I stopped putting them on a pedestal.” Respect endures, but now coexists with critical thought. Faith is becoming personal again, grounded in reason as much as reverence.

Engagement must remain informed and fair. Yax Mokwa warns that rejecting Hadith wholesale creates contradictions; Dr Musa adds that, in defending Hadith, some have erred by challenging the Qur’an itself. Balance, not bravado, should guide discourse.

Some, emphasise Masussuka’s deficiency in tajwīd-a valid concern, but it also reveals anxiety about authority in an age when eloquence can outweigh certification. This is the timeless contest between formal orthodoxy and popular reasoning.

Some insist that anyone engaging Masussuka’s ideas must have “joined him,” a framing that entirely misses the point. Intellectual honesty means being able to engage with ideas critically without necessarily subscribing to them.

Yet others dismiss the whole debate with sarcasm, comparing Masussuka’s current attention to a fleeting social-media trend, “just like Murja Kunya’s hype that soon faded away.” Both extremes, the quick judgment and the casual mockery-reveal a deeper discomfort with critical engagement itself, and a society still learning to distinguish curiosity from complicity.

Every time a new voice emerges, a familiar label returns. Some have already begun calling Masussuka “Maitatsine” or “Kala Kato,” invoking the 1980s radicals to delegitimise him by association. This is an easy but dishonest argument. The Maitatsine movement, violent and anti-intellectual, may have later inspired small Qur’an-only sects as highlighted by Yakubu Musa, but Masussuka is neither their descendant nor their mirror. His diction, reasoning, and style elegance reflect a disciplined scholar, not a street agitator. To equate him with Maitatsine is not analysis; it is evasion, a refusal to confront his arguments on merit.

Critics who pride themselves on being defenders of orthodoxy should remember that the mark of faith is composure. True scholarship persuades; it does not persecute. The more furiously one shouts “deviant,” the less confidence one shows in one’s own evidence.

As Bichiia Maisango observes, selective outrage has become the new hypocrisy. Silence follows when a preacher within the establishment errs; when an outsider challenges the system, the same voices demand state intervention. Such inconsistency exposes insecurity. It also forges unlikely alliances, as long-divided scholars begin to recognise a common threat to intellectual freedom.

I personally consider Masussuka not only a scholar and expert in the Qur’an, but also a philosopher-and for a long time, what we have lacked are true philosophers. Not mere preachers or polemicists, but thinkers who dare to question assumptions, connect faith with reason, and challenge the intellectual stagnation that has taken root in our society. Masussuka’s courage to think aloud, to provoke reflection rather than demand submission, fills a vacuum that has long existed in our public discourse.

Yet, Masussuka is not the storm; he is the mirror.

And what Northern Nigeria sees in that mirror is itself-ready, at last, to think.

May God establish us upon truth.