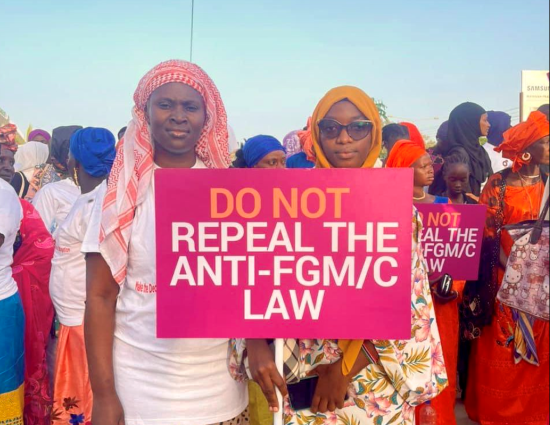

The Gambia’s parliament voted by a substantial margin on Monday to uphold a ban on female genital mutilation (FGM), defeating a Bill by conservative lawmakers and religious leaders.

Thirty four of the 53 MPs voted against the Private Members’ Bill introduced by MP Almameh Gibba from the Alliance for the Patriotic Reorientation and Construction (APRC), which was supported by Imam Abdoulie Fatty, a long-time advocate for FGM.

In April, the parliament supported the decision for the Bill to be referred to its business committee for more discussion. Less than 9% of MPs are female in the conservative, majority Muslim country and there was fear that the country’s 2015 ban on FGM was in jeopardy.

The decision was commended by UNICEF Executive Director Catherine Russell, UNFPA Executive Director Natalia Kanem, World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous, and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk.

“FGM involves cutting or removing some or all of the external female genitalia. Mostly carried out on infants and young girls, it can inflict severe immediate and long-term physical and psychological damage, including infection, later childbearing complications, and post-traumatic stress disorder,” according to the leaders in a joint statement.

The Gambia banned FGM in 2015 but enforcement of the ban is weak. Almost three-quarters of Gambian women are estimated to have been subjected to the practice, and almost half were cut before their 15th birthday.

ALSO READ NMC data: 3,173 Nigerian nurses, midwives moved to UK in 1 year

There has only been one FGM-related conviction in the past nine years, and that involved three women for cutting babies aged four to 12 months old, according to women’s rights activist Jama Jack. They received fines which were paid by Fatty via a public fundraising campaign, added Jack.The global leaders acknowledged “the fragility of progress to end FGM”.

“Assaults on women’s and girls’ rights in countries around the globe have meant that hard-won gains are in danger of being lost,” they added.

“In some countries, advancements have stalled or reversed due to pushback against girls’ and women’s rights, instability, and conflict, disrupting services and prevention programmes.

Continued advocacy

“That is why legislative bans on FGM, while a crucial foundation for interventions, cannot alone end FGM.”

They called for “continued advocacy to advance gender equality, end violence against girls and women, and secure the gains made to accelerate progress to end FGM”.

To do so, they recommended more engagement with communities and grassroots organizations; working with traditional, political, and religious leaders; training health workers, and raising awareness effectively about the harms caused by the practice.

ALSO READ Report highlights urgent intervention needs for Nigeria’s PHCs

“Supporting survivors of FGM remains as urgent as ever. Many suffer from long-term physical and psychological harm that can result from the procedure, and need comprehensive medical and psychological care to heal from the scars inflicted by this harmful practice.

“We remain steadfast in our commitment to support the government, civil society, and communities in The Gambia in the fight against FGM. Together, we must not rest until we ensure that all girls and women can live free from violence and harmful practices and that their rights, bodily integrity, and dignity are upheld.”

Control over women’s sexuality

FGM is practised mainly to “control” women’s sexuality. Around 90% of women in Somalia, Guinea and Djibouti are subjected to FGM.

Over 230 million girls and women alive today have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM), according to a report from the UN children’s agency, UNICEF. This is a 15% increase since eight years ago.

“The pace of progress to end FGM remains slow, lagging behind population growth, especially in places where FGM is most common, and far off-pace to meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal to eliminate the practice. The global pace of decline would need to be 27 times faster to end the practice by 2030,” UNICEF notes.

However, progress to prevent FGM is possible. In the past 30 years, FGM has declined in Kenya from moderate to low prevalence; Sierra Leone has dropped high to moderately high prevalence and Egypt is beginning to decline from a previously near-universal level.