A researcher, Dr Kolawole Aremu, has called for urgent public health action to curb the rapidly increasing spread of multidrug-resistant bacteria in Nigeria.

Aremu, a Research Associate at the Trans-Saharan Diseases Research Centre, Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida University (IBBU), made the call in an interview with reporters in Abuja.

He said the appeal followed a study conducted by his team on the prevalence of typhoid fever and factors driving multidrug resistance in Niger State.

According to him, Niger State was selected as a case study because of longstanding challenges related to poor sanitation and limited access to healthcare.

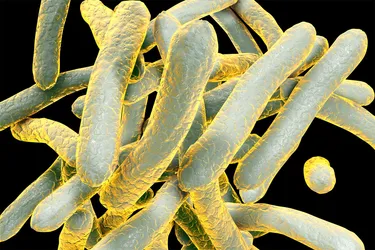

Aremu, who is one of the lead investigators, explained that the research adopted a cross-sectional study design involving young people aged 18 years and above. Stool samples were collected and analyzed to identify Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi.

He said the team, led by Prof. Musa Dickson, Director of the Trans-Saharan Diseases Research Centre at IBBU, tested the Salmonella isolates against selected commonly used antibiotics.

“Gentamicin and Levofloxacin showed relatively high effectiveness, with 78.5 per cent and 83.6 per cent efficacy respectively.

“However, resistance rates to older and frequently prescribed drugs were alarmingly high, with Chloramphenicol at 96.8 per cent, Tetracycline at 79.5 per cent and Amoxicillin at 100 per cent,” he said.

Aremu noted that the determination and interpretation of multidrug resistance were carried out in line with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines.

He added that the study examined the relationship between socio-demographic factors, clinical characteristics and multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi.

“Reports indicate that about 7.2 million cases of typhoid fever are recorded annually in sub-Saharan Africa.

“Nigeria’s situation is particularly worrying, as emerging evidence shows very high infection rates and shrinking treatment options due to antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

“Our data show complete resistance to first-line antibiotics, meaning these drugs are no longer effective for many patients,” Aremu said.

He identified poor sanitation, contaminated water sources and the widespread misuse of antibiotics as major contributors to the problem.

According to him, participants who relied on tap water recorded a 57.1 per cent infection rate, compared to 25.6 per cent among borehole users, suggesting serious contamination of public water systems.

He also linked self-medication and unrestricted access to antibiotics—especially Amoxicillin and Clavulanic acid combinations—to the rising levels of multidrug resistance.

Aremu said young adults aged between 18 and 27 years bore the highest disease burden, likely due to frequent exposure in crowded schools, markets and social settings with inadequate sanitation.

He warned that untreated or poorly managed infections could lead to severe complications, prolonged hospitalization and increased mortality.

The researcher stressed the urgent need for improved Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) infrastructure, stricter regulation of antibiotic sales and widespread community health education.

He added that public health experts had called for more responsible prescribing practices in line with global antimicrobial resistance containment guidelines.

“Given the rapid emergence of drug-resistant strains, we are advocating the establishment of sustained disease surveillance systems to track resistance patterns and guide treatment protocols,” he said.

Aremu cautioned that without coordinated and timely interventions, Nigeria risked a major public health emergency driven by the combined threats of typhoid fever and antimicrobial resistance.

Other contributors to the study include Prof. Stella Smith and Enyo Sule of the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research; Dr Samuel Abah of the Coventry University Group, London Campus; Dr Salamatu Mambula-Machunga of the University of Abuja; and Dr Hussaini Majiya of IBB University, among others.