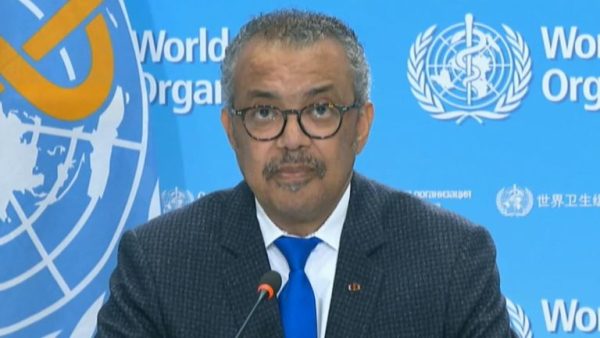

The Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has criticized the United States’ decision to reject recently adopted amendments to the International Health Regulations (IHR), describing it as being based on “inaccuracies.”

The amendments, agreed upon by consensus during the 2024 World Health Assembly — and with active participation from the U.S. — aim to enhance the global response to public health emergencies, drawing lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We regret the US decision to reject the amendments adopted by consensus by the World Health Assembly in 2024 – including by the US, as the US played an active role in developing and negotiating those amendments together with other countries,” Tedros stated.

U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Secretary of State Marco Rubio argued that the new IHR rules would “significantly expand” the WHO’s authority over global public health responses and influence U.S. domestic decision-making. The two officials echoed claims outlined in Project 2025, a conservative policy agenda linked to the Trump political orbit, which raises concerns over international governance in health.

In response, Tedros moved to clarify that the WHO does not possess the authority to impose health mandates such as lockdowns or travel bans. “The amendments are clear about member states’ sovereignty,” he emphasized. “WHO has never had the power to mandate lockdowns… member states have the power to do so if they see the need.”

He further explained that the 2024 amendments were not designed to empower the WHO but rather to improve cooperation among countries during future pandemics. “They were proposed, negotiated, and adopted by member states based on the learnings from the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Regarding claims of WHO susceptibility to political influence and censorship — particularly from China — Tedros reaffirmed that the organization remains impartial. “The WHO is impartial and works with all countries to improve people’s health,” he said, warning that using disease outbreaks for propaganda “would be destructive and disastrous.”

Professor Lawrence Gostin of Georgetown University, who helped draft the IHR, also rejected the U.S. officials’ claims. “The IHR facilitates rapid detection and response. It actually promotes accurate information and protects civil liberties,” said Gostin. “And it certainly does not affect US sovereignty. These are all falsehoods.”

The IHR were initially revised following the 2005 SARS outbreak. The latest amendments introduced a formal definition for “pandemic emergency” to trigger quicker and more unified global action. They also include measures to promote equity — especially in access to vaccines, treatments, and funding for developing countries — and propose a new Coordinating Financial Mechanism to support pandemic preparedness.

Although the revised regulations suggest forming a States Parties Committee to assist countries in implementation, this body is “non-punitive” and intended to encourage cooperation rather than enforcement.

Ironically, the U.S. had served as vice-chair of the Working Group on Amendments to the IHR (WGIHR), which was led by Dr. Ashley Bloomfield of New Zealand and Dr. Abdullah Assiri of Saudi Arabia.

“The experience of epidemics and pandemics, from Ebola and Zika to COVID-19 and mpox, showed us where we needed better public health surveillance, response and preparedness mechanisms,” said Bloomfield.

Assiri added that the IHR amendments “strengthen mechanisms for our collective protections and preparedness against outbreak and pandemic emergency risks.”

Despite the international consensus on the need for stronger global health regulations, the U.S. rejection of the amendments marks a significant deviation — one rooted, according to the WHO, in misinformation.