For 36 years, Tayo Oredola-Elegbede has lived with sickle cell disease. She has endured the pain, the hospital visits, and the societal stigma that comes with the condition. But rather than let it define her, she has turned her experience into advocacy — educating others on the importance of genotype awareness and fighting against the discrimination that sickle cell warriors face daily.

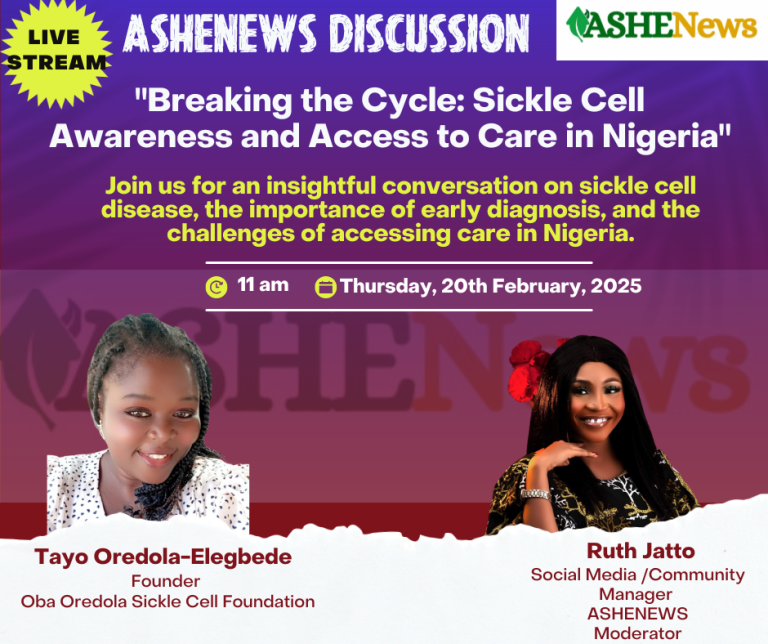

During a recent ASHENEWS Facebook Live discussion themed “Breaking the Cycle: Sickle Cell Awareness and Access to Care in Nigeria” which was moderated by Ruth Jatto, ASHENEWS’ Social Media and Community Manager, Oredola-Elegbede, founder of the Oba Oredola Sickle Cell Foundation, shared her story and insights on how Nigeria can break the cycle of sickle cell disease.

She emphasized two key solutions: widespread premarital genotype screening and the urgent need to eliminate stigma.

According to Oredola-Elegbede, greater awareness and early genetic testing could significantly reduce the prevalence of sickle cell disease in Nigeria stressing that genotype compatibility should be a key consideration before marriage to prevent children from inheriting the disease.

The gamble of genetic compatibility

Sickle cell disease is inherited when both parents pass on an abnormal hemoglobin gene. If both parents have the sickle cell trait (AS or AC), there is a 25 per cent chance in every pregnancy that their child will inherit the full-blown sickle cell disease (SS).

Yet, many couples only discover this risk when it is too late—when they already have a child battling the painful realities of sickle cell. She lanented that some know they are carriers but go ahead and get married as they would cite faith, gamble and trial and unproven answers by unprofessionals.

“Too often, love is placed above logic,” Oredola-Elegbede said. “Couples get married without checking their genotype, only to find out later that their children are the ones to suffer. We need to make genotype screening a mandatory conversation before marriage.

“Genotype screening should not be taken lightly. It is a crucial step in preventing unnecessary pain and suffering. If more people knew their genetic makeup before choosing a life partner, we could drastically reduce the number of children born with sickle cell disease,”

Despite increased awareness, misconceptions remain. Many believe that since a couple with AS-AS compatibility has a 75 per cent chance of having a child without sickle cell in each pregnancy, they can “try their luck.”

“But for the 25 per cent born with the disease, that gamble comes with a lifetime of health challenges, including chronic pain, organ damage, and a reduced life expectancy. Some couple end up having majority of their children becoming sickle cell carriers.”

Living beyond the stigma

Beyond the medical challenges, people living with sickle cell face social stigma that affects their education, career prospects, and relationships. Many are considered “weak” or “incapable” of handling demanding jobs. Some women are told they cannot carry pregnancies, while men with sickle cell often struggle to find partners willing to marry them.

“There’s so much misinformation about sickle cell,” Oredola-Elegbede noted. “People think we are always sick, that we can’t live long, or that we are a burden. But we are lawyers, doctors, journalists, and business owners. We thrive despite the odds.

“Stigma is the reason why several sickle cell warriors are not coming out to openly seek care and talk about their condition. People living with sickle cell can get to live a normal life. We can work; we are not lazy people. People should start stigmatizing us.

“It is not a crime that we are living in a condition that we do not know anything about. We were just born into it because of two people, two ignorant people, two misled people, two people who claimed to be in love and wanted to take the gamble but did not have an idea id what they were doing but we are still punished for it, how fair is that?”, she questioned sadly.

This stigma, she explained, makes it even harder for individuals with sickle cell to access care pointing that some hospitals are ill-equipped to handle sickle cell crises, while financial constraints force many families to rely on traditional remedies instead of proper medical treatment.

Oredola-Elegbede pointed that due to the stigmatization, several families who have a person living with sickle cell tend to live in denial and do not allow anyone outside the family to know.

She added that some organizations do not have the patience and time to employ someone living with sickle cell disease while giving an example of herself, “my last job was taken away from me, not because i do not have the mental capacity to work but my status did not make me as productive as they wanted.

ALSO READ: Can milk and calcium-rich foods reduce colorectal cancer risk?

“At the end of the day, i was told that it was not a charity organization but a business. I understand that it is a business but who wants to understand that I want to do more than I was doing but the way I was wired was not allowing me.”

A call for change

Oredola-Elegbede’s Foundation, Oba Oredola Sickle Cell Foundation, is dedicated to raising awareness about sickle cell, providing support for affected families, and advocating for government-backed policies to improve access to healthcare.

She believes Nigeria needs a national strategy that prioritizes genotype education, ensures reliable testing, and makes treatment more affordable.

“We need to stop treating sickle cell as an individual problem. It is a national issue. If we can normalize genotype discussions and promote empathy rather than discrimination, we can prevent unnecessary suffering.”

As Nigeria remains the country with the highest number of sickle cell births globally—an estimated 150,000 annually—advocates like Oredola-Elegbede are pushing for action. She hopes that through continued awareness, fewer children will be born into pain, and those already living with sickle cell will be treated with dignity and respect.

Breaking the cycle

The conversation around sickle cell must shift from stigma to solutions. Premarital genotype screening should be embraced not as an obstacle to love but as a responsible step toward a healthier future. And for those living with sickle cell, the focus should be on support, not discrimination.

“Sickle cell does not define us. What defines us is how we rise above it,” Oredola-Elegbede said.

She noted that if Nigeria is to break the cycle, it will take education, compassion, and a collective commitment to change urged the government and civil society organizations to launch more awareness campaigns to educate the public on the realities of sickle cell disease and the importance of support rather than discrimination.

“Awareness can save lives. The more people understand sickle cell disease and make informed choices, the fewer children will have to suffer from it,” Oredola-Elegbede stressed.